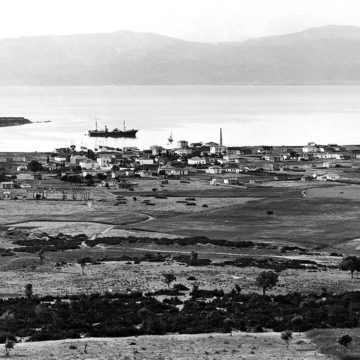

Nea Psara – 19th c. Eretria

Neo-classical architecture (19th c.)

Neo-classical architecture became fashionable in Greece after Independence. Initially promoted by the first governor of Greece, Ioannis Kapodistrias (1827-1831), it became dominant under Otto I, King of Greece (1832-1862) and his successor, George I (1863-1913). Journeys in Greece undertaken by the Englishmen James Stuart and Nicholas Revett between 1751 and 1754, and by the Frenchman Julien-David Le Roy between 1754 and 1755, were important landmarks in this development. Once Greek sovereignty was won, this style was imported into Classical lands by philhellenes and accepted as the national style not only by the Greek population but by Greeks living abroad in diaspora.

Neo-classical architecture was at first confined to public buildings and the residences of those connected with the government and the Greek aristocracy. But very soon it spread to the private architecture in centers like Athens and Hermoupolis, and eventually became the favorite architectural style in other areas.

Ferdinand PAJOR, Ερέτρια-Νέα Ψαρά. Το χρονικό μιας πολιτείας. Athens 2010 (Melissa Ed.).

Ferdinand Pajor, Eretria – Nea Psara. Eretria – Nea Psara. Eine klassizistische Stadtanlage über der antiken Polis. ERETRIA XV. Goillon 2006 (inFolio ed.).

Public buildings

According to Eduard Schaubert’s project, Eretria was supposed to become an important regional urban center. However, several factors, not only economic and social, but also natural (marshes), considerably slowed the development of this city. Nonetheless, Eretria still has interesting Neoclassical edifices. Among the public buildings indicated on the 1834 plan, only the oldest, the church of Aghios Nikolaos, remains on its original site, between Hegelochou Tarantinou street and Aristogeitonos Philoxenou street. Probably constructed in 1835, this church was originally a simple edifice with a single nave and a small apse at its east end. Over time, it was enlarged and a spire and a narthex were added on the west side. Despite its simplicity, it is typical of Neo-classical religious architecture in its east-west orientation, in contrast to the Byzantine tradition, in which churches have a central-plan building.

It is interesting to note that the main church, which was to be built at the center of the city, was supposed to be Byzantine in style. Since Eretria did not develop much during the 19th century, public buildings were either not built or immediately fell into ruins, like the naval school south of the ancient Theater. However, the old school, located on the bay of the port, was probably constructed at the turn of the 19th to the 20th centuries. It is not only a good example of Neo-classical architecture, but also a testimony to the government’s political will to promote schooling. This can already be seen in Schaubert’s plan, in the complex constituted by the naval school and the library.

Secular architecture

Eretria also posseses a series of private buildings that are still more typical of modern Greece’s architectural renaissance than are its public buildings. This architecture is characterized by one- or two-level structures of modest size. The edifices stand along the building lines of the streets and are therefore located at the front of large lots. Each building has a garden behind it. The old buildings are usually constructed of poros buildingstones with a few dressed stone blocks. The latter, which sometimes come from ancient buildings, serve to reinforce foundations or corners. According to the archaeologist Ludwig Ross, the ancient blocks were supposed to be reserved for public buildings. For economic reasons, marble appears only rarely in private architecture, notably in balconies. Another important construction material is brick, used when a building is being raised or for the construction of the rows of contiguous houses built for refugees in 1922. The list of the principal construction materials also includes unfired brick, used especially for rural outbuildings, but also, although less frequently, for dwellings that could have two levels. Buildings are usually covered with stucco and painted white, yellowish or red ochre, or gray.

A sober and elegant style

The Neo-classical buildings are characterized by the simplicity of their façades. The latter are limited to pilaster strips in stucco, which resemble the marble corners or pilasters of prestigious structures. The doors and windows, which are generally arranged symmetrically, are emphasized by rectangular frames that are also stuccoed. Buildings with two levels repeat this pattern, though in a more luxurious manner: the lower level may be in stucco or in rough, unfinished masonry, and the two levels are separated by a stringcourse or band. It is the cornice that exhibits a typical Neo-classical element: the architrave. Purely decorative, it is supported by pilasters, also stuccoed. The Neo-classical buildings have a hip or gable roof, covered with Laconian tiles and ornamented with antefixes.

The interplay between the horizontal axis and the vertical articulations gives these buildings a certain rigor. The latter is nonetheless attenuated by the care given to details. A few window frames, which may also be made of wood, are ornamented with fascias and crossettes, and the window ledges are ornamented by receding tables. More sumptuous buildings also have a balcony on the main façade, characterized by guardrails in forged or cast iron, which testify to a high level of craftsmanship that is also observed in the grillwork of gardens and doors.

In addition to Neo-classical buildings of the urban type, Eretria, which was long a farming town, has rural buildings that are also inspired by Neoclassical architecture, though their architectural conception is less regular. Similarly, the little houses of the refugees from Asia Minor, despite their vernacular aspect, also have Neoclassical elements, as is shown by the doors and windows.

A Heritage in danger

Eretria’s architectural patrimony is an important testimony to the history of modern Greece, and in particular to the settlement of refugees from Psara and Asia Minor. Unfortunately, with the development of tourism in the 1960s, it was greatly changed, and the buildings that remain are threatened by new construction. It is too often forgotten that the architecture of Eretria is intimately connected with the plan of 1834 (alignments and gardens). It is also appropriate to point out that Neo-classical architecture in the area is of a level comparable to that of private buildings in Athens. Given the close connection between the plan for Eretria and the initial projects for Athens and the Piraeus, also drawn up by Schaubert, Eretria’s Neo-classical structures as a whole deserve to be better protected.

Text by Ferdinand Pajor